October 27, 2011

Creating a safer synthetic version of the anticoagulant heparin can be done in as few as ten steps thanks to a breakthrough made by scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute that promises a purer, less expensive drug with fewer side effects.

Creating a safer synthetic version of the anticoagulant heparin can be done in as few as ten steps thanks to a breakthrough made by scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute that promises a purer, less expensive drug with fewer side effects.

In a paper published in the November issue of the journal Science, a team led by Jian Liu, PhD, of the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy and Robert J. Lindhardt, PhD, of RPI document a technique that combines enzymatic and chemical processes to synthesize a simplified version of heparin in significant quantities in just ten to twelve steps. Fondaparinux, the only synthetic heparin on the market, takes forty to fifty steps to make in a purely chemical process.

Heparin is most often used during and after such procedures as kidney dialysis, heart bypass surgery, stent implantation, indwelling catheters, and knee and hip replacement to prevent clots from forming. Heparin is extracted from animal tissue, chiefly from cows and pigs. Its side effects include uncontrolled bleeding and thrombocytopenia (too few platelets in the blood). The worldwide sales of heparin are estimated at $4 billion annually.

The natural form of the drug was in the spotlight in spring 2008 when more than eighty people died and hundreds of others suffered adverse reactions to it, leading to recalls of heparin in countries around the world. Authorities linked the problems to a contaminant in raw natural heparin extracted from pig intestines in China.

“A man-made version of heparin that can be made inexpensively under laboratory conditions is the key to preventing a recurrence of the 2008 tragedy,” Liu says.

“Natural heparin is a mixture of very large molecules,” he says. “It is very difficult to synthesize homogenous heparin, but we have been able to recreate just the fragment that is responsible for the anticoagulant activity,” says Liu. “The product is a highly efficient molecule that carries none of the extra baggage of natural heparin that can cause dangerous side effects.”

Before 2008 unfractionated heparin, the most commonly used variety, was only about one dollar per dose. However, increasingly stringent manufacturing standards have increased the price of raw heparin tenfold in recent years. A more refined version of heparin called low molecular weight heparin is now the most commonly used anticoagulant in the developed world because of its reduced risk of side effects. A thirty-to-forty milligram dose used to prevent clots during knee or hip surgery runs $25 to $35. Fondaparinux costs $50 to $60 per dose when used for the same purpose.

“It is difficult to predict what the actual manufacturing costs of our version of synthetic heparin would be, but I don’t think that a cost similar to low molecular weight heparin is unrealistic,” Liu says. “If you’re talking about large-scale production, our method is the way to go.”

Researchers were able to produce 50 milligrams for their study and could have easily made more of the drug, which could be called ultralow molecular weight heparin, Liu says.

Liu is a professor in the Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry. Lindhardt is the Ann and John H. Broadbent Jr. ’59 Senior Constellation Professor in the RPI Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology. The other authors of the study from the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy are postdoctoral research associates Yongmei Xu, PhD, and Renpeng Liu, PhD; Haoming Xu, a UNC sophomore majoring in biochemistry; and first-year pharmacy student Juliana Jing. Additional authors are Sayaka Masuko of RPI and Madje Takieddin, MS, and Shaker Mousa, PhD, MBA, of the Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.

The research described is supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Latest News

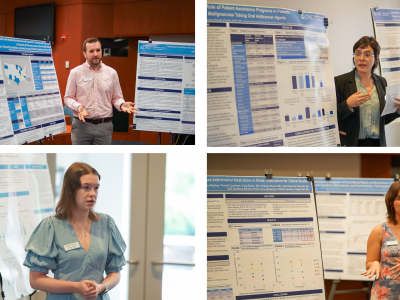

RASP poster presentations capture student research

Delesha Carpenter promoted to full professor