October 15, 2010

The UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy has received a $6.6 million federal contract to complete work on an easily-administered medication that can help clear radioactive elements from the body.

The contract, awarded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, has tasked UNC researchers led by principal investigator Michael Jay, PhD, with creating a form of diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid, commonly known as DTPA, that can be administered orally and distributed quickly to people affected by a nuclear accident or dirty-bomb attack. Dirty bombs are explosive devices designed to spread radioactive contamination.

DTPA is a chelating agent that has been used for many years as an intravenous injection to treat patients exposed to certain radioactive elements and other metals. Chelates are molecules that wrap around metals, such as certain isotopes, making it easier for the body to flush them out.

“DTPA is wonderful delivered as an injection, but the approved methods of administration do not lend themselves to a mass-casualty situation,” says Jay, a Fred Eshelman Distinguished Professor in the Division of Molecular Pharmaceutics.

Michael Jay, PhD, explains his plutonium-seeking pill

Jay has spent the last five years working on the project. In its natural form, less than 1 percent of DTPA taken orally is absorbed by the body. He modified the DTPA molecule to create a prodrug—or inactive form—that could be absorbed easily through the intestinal wall and then be converted to DTPA in the bloodstream. Once in the body, DTPA goes after radioactive isotopes of plutonium, americium, and curium, which usually lodge themselves in the bones and in the liver. The new prodrug has worked well in biological models with nearly 100 percent being absorbed and converted to DTPA, he said. However, the prodrug is a challenging molecule from a drug maker’s perspective.

“It cannot be made into tablets, is not particularly stable, is difficult to chemically analyze, and tastes awful,” Jay says.

The goal for this phase of Jay’s project is to complete the work that will lead to the submission of an investigational new drug application, which is needed to begin clinical trials in humans.

Jay’s co-investigators on this project are two of his colleagues in the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy: Russell Mumper, PhD, the John A. McNeill Distinguished Professor; and associate professor Bill Zamboni, PharmD, PhD. Zamboni is the director of the GLP Analytical Facility funded by the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, which will be heavily involved in testing Jay’s drug with the help of other North Carolina companies and the Lovelace Respiratory Research Center in New Mexico.

Latest News

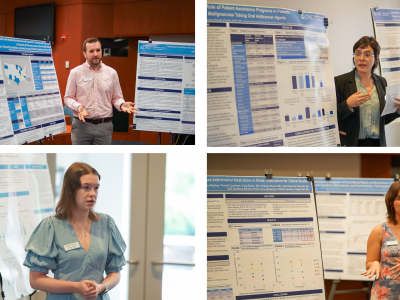

RASP poster presentations capture student research

Delesha Carpenter promoted to full professor