November 16, 2011

Malaria treatment in African nations could be more effective and less expensive if drug-policy makers paid more attention to how genetics affect a patient’s response to malaria treatments, say researchers at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy.

The researchers looked at how malaria is normally treated in malaria-endemic countries and then checked to see whether there was genetic information available that suggested that a different drug be used. The researchers’ recommendations were published in a commentary in the January issue of the Bulletin of the World Health Organization.

“As part of the Pharmacogenetics in Every Nation Initiative, we looked at malaria because it is one of the most common diseases in the developing world and realized there is a pharmacogenetic difference in how patients metabolize the four drug combinations commonly used to treat the disease,” says Mary Roederer, PharmD, a clinical assistant professor at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy and lead author of the paper. She is also a member of the School’s Institute for Pharmacogenomics and Individualized Therapy.

For example, Ghana experiences more than five million cases of malaria each year and uses amodiaquine (combined with artesunate) as its first-line treatment. However, 1.5 percent of the population has a mutated form of the enzyme CYP268 and doesn’t metabolize the drug very well, leading to adverse drug reactions and less effective treatment. The researchers estimate that Ghana could save approximately $43,000 in the cost of wasted medicine alone by switching to a different treatment, assuming there are no drug-resistant strains of the disease involved.

Ministries of health in Africa do not typically use pharmacogenetic information when making drug decisions, Roederer says, and availability and cost are usually the two main factors when selecting a treatment. However, Zanzibar, part of Tanzania, did switch to combination of artemether and lumefantrine and the significant percentage of the population who are poor metabolizers of amodiaquine may have played a part, Roederer says. .

“While there is a tremendous lack of data in most of the malaria-endemic countries, we want to highlight how pharmacogenetics can contribute to formulary decision-making in developing countries,” Roederer says. “We very much want to identify ways to increase the amount of data available on the incidence of genetic variation in order to inform drug policy decisions.”

The authors suggest that researchers doing studies in similar areas get the consent of participants to also allow genetic analysis of their blood and tissue samples. Without that consent, many opportunities to gather additional information are wasted, Roederer says.

“If study designers did that from the get-go, then the samples could be used for multiple purposes, and a single person could make an even greater contribution to the advancement of health care,” she says.

Roederer’s coauthors on the commentary are Howard McLeod, PharmD, Eshelman Distinguished Professor and IPIT director; and Jonathan Juliano, MD, clinical assistant professor of medicine in the UNC Center for Infectious Diseases at the UNC School of Medicine.

Latest News

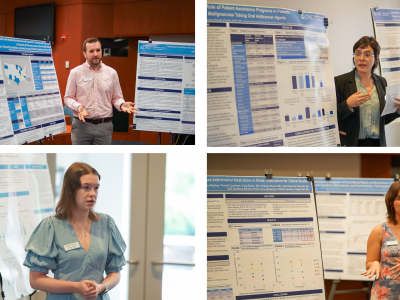

RASP poster presentations capture student research

Delesha Carpenter promoted to full professor