December 18, 2009

Development of an AIDS vaccine is struggling. Topical treatments aimed at stopping HIV have made little progress. Angela Kashuba, PharmD, believes that antiretroviral drugs are the best hope for halting the spread of AIDS, especially in the developing world.

“I and the scientists I work with believe antiretrovirals are probably the most rational approach for preventing HIV infection,” she says. “We think they are going to be the key for stemming the epidemic of HIV.” Kashuba is an associate professor at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy and director of the Clinical Pharmacology and Analytical Chemistry Core of the UNC Center for AIDS Research.

The National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases has awarded her a $100,000 planning grant for her proposal, “Preventing HIV Infection in Women: Targeting Antiretrovirals to Mucosal Tissues.” The planning grant is the first step in a process that Kashuba hopes will result in clinical trials to develop a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model that can predict the right dosage of antiretroviral drugs needed to achieve the optimum concentration of those drugs in the body to prevent infection by HIV.

“I am focused on providing some rational clinical pharmacology to the HIV-prevention community to choose the right drugs, the right doses, the right combination of drugs, the right regimen to put into a clinical trial for HIV prevention,” Kashuba says. “The fact that NIAID has awarded this grant means that they believe in this approach and are very interested in working with us.”

Kashuba says she is planning a series of clinical studies in HIV-negative women to evaluate the drug exposure in mucosal surfaces that are susceptible to HIV infections (vaginal, rectal, and cervical tissue). Using these data along with data generated from a novel tissue-culture system that can be infected with various strains of HIV, she would then develop a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model that will give researchers the proper dosage needed to achieve the desired concentration of drugs in the tissue. In other words, the model would tell scientists how much medicine a person needed to take to protect themselves from HIV.

“Although we know the effective concentrations we need to treat someone for HIV, we’ve never worked out what concentration of drugs we need to prevent HIV infection,” Kashuba says. “We’ve developed a rather novel model where we can infect human tissue with HIV, put drugs on the tissue, and define for the first time the right concentration protect that tissue against HIV.”

There are currently seven infection-prevention clinical trials going on around the world using one or two antiretroviral drugs, drugs that have been tested in animals but at much higher doses than the ones the approximately 10,000 participants are receiving, she says.

“We have no preliminary data about whether these drugs at the doses given are actually going to work. While I am hopeful that at least one of these approaches will have some effect, the results probably will not be optimal.”

Kashuba’s work is focused on protecting uninfected people, particularly women in the developing world who for social, cultural, or religious reasons cannot take steps to protect themselves that would be apparent to a partner. Kashuba is collaborating on the project with Myron Cohen, MD, the J. Herbert Bate Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Microbiology, Immunology, and Public Health and director of the UNC Center for Infectious Diseases; clinical assistant professor Kristine Patterson, MD, and assistant professor Gretchen Stuart, MD, MPH, all from the UNC School of Medicine, as well as Nicholas Shaheen, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine and epidemiology in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Latest News

Dean Angela Kashuba receives Carolina Alumni Faculty Service Award

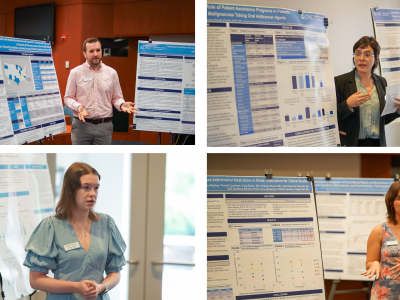

RASP poster presentations capture student research