February 4, 2020

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the flu vaccine for the 2018-19 season was only 29 percent effective.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the flu vaccine for the 2018-19 season was only 29 percent effective.

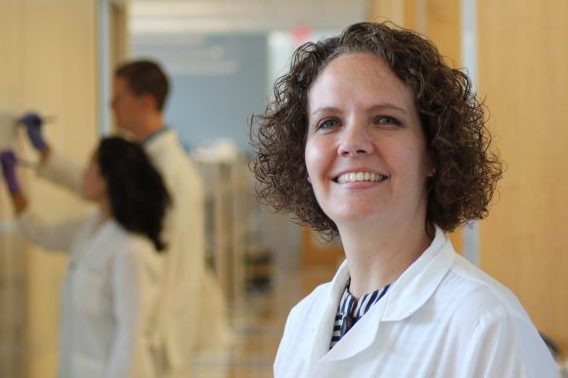

Kristy Ainslie, Ph.D., wants to improve that number with the help of a $2.8 million grant.

“All of us have been exposed to influenza,” she said. “When it happens to the sick, the young or the old, then it can become lethal.”

Ainslie, a professor and vice chair of the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy’s Division of Pharmacoengineering and Molecular Pharmaceutics, recently received a prestigious R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health. The grant will support research for a more broadly acting influenza vaccine over the next five years.

Typically, researchers predict which viral strains will be most prevalent months before the flu season starts, but this guess is never completely accurate. Also, during the time the vaccine is manufactured the influenza virus mutates and the viral strains selected are less effective as a vaccine, Ainslie said.

Ainslie has a background in chemical engineering and scientific outreach. Her lab focuses on applied immunology and new therapies for infectious and auto-immune diseases. She said she became interested in improving the influenza vaccine because she wanted to develop something that could better protect people than the current vaccine.

With the R01 grant, she aims to target the three most lethal influenza strains and develop one vaccine to protect against all of them. A co-investigator from the University of Georgia has been developing antigens that combine years of flu data. These antigens train the immune system to better protect against viruses that have changed over time. By putting these antigens and existing adjuvants (which enhance the body’s immune response) into biopolymer microparticles she hopes to create a stronger immune response and invoke immune memory to improve the protection developed from the vaccine.

In addition to developing a vaccine that can improve protection, the proposed approach could shorten the time it takes to make the vaccine as well as the number of times the vaccine needs to be given.

“You can develop a vaccine more rapidly because it doesn’t have to be unique each year,” she said. With this approach, there is the potential to shift the influenza vaccine from a yearly shot to more of a childhood immunization schedule.

Ainslie hopes that the pre-clinical models from this study will translate well to future clinical trials.

Latest News

RASP poster presentations capture student research

Delesha Carpenter promoted to full professor